Indigenous Peoples: Defending an Environment for All

Still Only One Earth: Lessons from 50 years of UN sustainable development policy

Lands inhabited by Indigenous Peoples contain 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity. Indigenous Peoples’ traditional knowledge and knowledge systems are key to designing a sustainable future for all. International environmental negotiations need to go beyond tokenistic participation of Indigenous Peoples to a genuine integration of their worldviews and knowledge. Respecting and promoting their collective rights to their lands, self-determination, and consent is vital to strengthening their role as custodians of nature and agents of change. (Download PDF) (See all policy briefs) (Subscribe to ENB)

"Only when the last tree has died and the last river has been poisoned and the last fish has been caught will we realize that we can not eat money.” Chief Seattle

There are approximately 370 million Indigenous Peoples today representing thousands of languages and cultures. Indigenous lands make up around 20% of the Earth’s territory, containing 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity—a sign Indigenous Peoples are the most effective stewards of the environment. In contrast with models of individual ownership, privatization, and development that have led to climate change, pollution, land degradation, and biodiversity loss, Indigenous Peoples have practiced sustainability for centuries.

There is no formal definition of Indigenous Peoples in international law. According to one definition, Indigenous Peoples are those who lived on their lands before colonial powers claimed the land through problematic legal doctrines of conquest, occupation, or other means. This resulted in dispossession, oppression, and creation of dependency. The international remedy to colonization is the right to self-determination, which is set out for Indigenous Peoples in Article 3 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

A modern understanding of who is Indigenous is based on different elements. A key one is self-identification as Indigenous and recognition and acceptance by the group as one of its members. This is well established, including in the International Labour Organization Convention Nº 169, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination and in Article 33 of UNDRIP, adopted in 2007 by the UN General Assembly. Other important elements to identify Indigenous status include a strong link to territories and natural resources, and distinct social, economic, or political systems.

At the First International Conference of Indigenous Peoples in 1975 in Port Alberni, British Columbia, Canada, Indigenous representatives decided to use the term “Indigenous Peoples” to refer to themselves at the international level. They adopted the 1975 Solemn Declaration where they refer to themselves as those “who have a consciousness of culture and peoplehood on the edge of each country’s borders and marginal to each country’s citizenship.” They did not feel represented by country governments at the United Nations. Almost 50 years after intense advocacy efforts in the international arena, the use of the term “Indigenous Peoples” is well-established at the UN, as is their right to self-determination, which is recognized not only in UNDRIP, but also in many other international human rights instruments and multilateral environmental agreements.

The Aboriginal vision of property was ecological space that creates our consciousness, not an ideological construct or fungible resource...Their vision is of different realms enfolded into a sacred space...[the] notion of self does not end with their flesh, but continues with the reach of their senses into the land but continues with the reach of their senses into the land

Recognition of the right to self-determination of Indigenous Peoples is vital to protect their traditions, and their social, cultural, economic, and political characteristics that are distinct from those of dominant governments. Indigenous Peoples hold unique knowledge systems and practices for the sustainable management of natural resources. Many have a special relationship with the environment, the land, and all living things. Against this backdrop, the Western view of land, natural resources, and nature in a commodified and more tradable manner stands in stark contrast.

Indigenous Peoples’ Participation at the UN

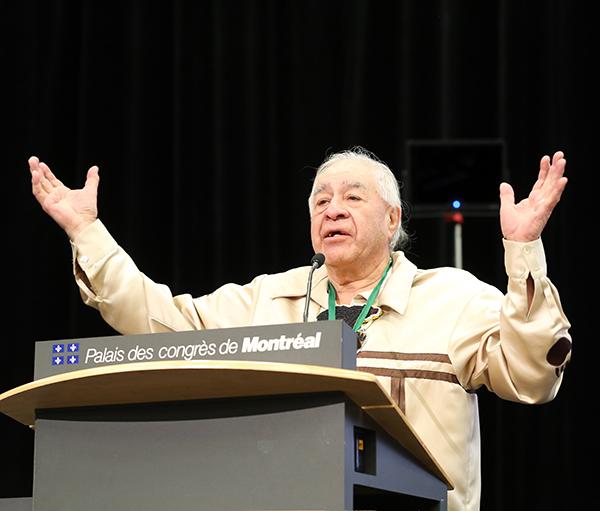

In 1923, Chief Deskaheh of the Iroquois Confederacy brought the Iroquois dispute with the Canadian Government over their sovereignty to the League of Nations. The dispute was dismissed as the League considered it a domestic matter (Anaya, 1996). Despite opposition from some states, including legislative prohibitions on organizing around land issues, Indigenous Peoples again ventured into the international arena half a century later. In 1972, Grand Chief George Manuel from the National Indian Brotherhood in Canada was part of the Canadian delegation to the UN Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm, Sweden (Crossen, 2017). This was the beginning of Indigenous participation in international environmental negotiations. However, the resulting Stockholm Declaration and Action Plan did not acknowledge Indigenous Peoples, demonstrating the need for more organizing. As a result, Manuel founded the first modern pan-Indigenous organization, the World Council of Indigenous Peoples (WCIP).

In 1977, the first UN conference with Indigenous delegates participating alongside states, the International NGO Conference on Discrimination Against Indigenous Populations in the Americas, convened in Geneva, Switzerland. It had far-reaching repercussions, including the adoption of the “Declaration of Principles for the Defense of the Indigenous Nations and Peoples of the Western Hemisphere.” It also resolved “to observe October 12, the day of so-called ‘discovery’ of America, as an International Day of Solidarity with the Indigenous Peoples.” This conference also recommended creating the UN Working Group on Indigenous Populations (WGIP), which came to fruition in 1982. The WGIP gave Indigenous Peoples visibility at the UN (Dahl, 2012). Moreover, it provided a space for Indigenous Peoples to substantially contribute to the draft of UNDRIP, facilitated by Erica-Irene Daes, who played a pivotal role in promoting the Indigenous cause, both within and beyond the WGIP.

The process of drafting UNDRIP took almost three decades of intense and complicated negotiations. From the outset, controversial issues included the recognition of the right to self-determination, collective land rights, and the requirement of their free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) to major projects on their lands and territories. UNDRIP enshrines these three elements and has since guided developments on Indigenous rights across international negotiations.

Indigenous Peoples wanted to create a permanent forum as high in the UN hierarchy as possible, with a mandate beyond human rights. This was achieved in 2001, when the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) was established under the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). UNPFII began to integrate Indigenous Peoples as participants with similar rights to states for the first time in UN history (Dahl, 2012). Eight members of the UNPFII are appointed by governments and eight by the president of ECOSOC on the recommendation of Indigenous Peoples’ representatives. At the UNPFII, Indigenous Peoples’ appointed experts adopt resolutions, and provide recommendations to governments and UN bodies. The UNPFII, together with the appointment in 2001 of a Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the 2007 Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples under the UN Human Rights Council, have expanded awareness on the views and situation of Indigenous Peoples.

Challenging the Prevailing Discourse on Sustainable Development

Indigenous Peoples challenge prevailing Western discourses, such as on human rights and on the normative foundations of the international world order and the UN (Tauli-Corpus, 1999). The worldviews of Indigenous Peoples have also challenged the prevalent discourse on sustainable development, calling for recognition and respect of their traditional knowledge and collective rights to use and control the lands and natural resources that they depend on and strive to protect.

Indigenous Peoples occupied a prominent role in the preparatory sessions for the 1992 Conference on Environment and Development (Earth Summit) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Tauli-Corpus, 1999). Their lobbying and organizing efforts, which began in Stockholm 20 years earlier, resulted in a wider recognition of Indigenous Peoples in Agenda 21, the programme of action adopted in Rio. In addition to being referenced throughout the 40-chapter action programme, Chapter 26 explicitly called for establishment of a process to empower Indigenous Peoples and their communities through various measures. Chapter 26 also called for the involvement of Indigenous Peoples and their communities at the national and local levels in resource management and conservation strategies to support and review sustainable development strategies.

We also recognize the importance of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in the context of global, regional, national and subnational implementation of sustainable development strategies.

Since 1992, Indigenous Peoples have engaged directly in UN processes on sustainable development, including in the Commission on Sustainable Development (1993-2013) and its successor, the High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development. At the UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20) in 2012, the outcome document, “The Future We Want,” recognized the importance of the participation of Indigenous Peoples in the achievement of sustainable development.

Indigenous Peoples’ organizations also worked on the sidelines of the sustainable development process adopting a Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth at the World People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth, in Cochabamba, Bolivia, in 2010. This declaration stands in opposition to the green economy and growth narrative, which later underpinned the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Protecting Biodiversity

Indigenous Peoples are recognized in the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) as essential to reaching the convention’s objectives (Schabus, 2017). In CBD Article 8(j), in particular, parties agree to respect, preserve, and maintain the knowledge, innovations, and practices of Indigenous Peoples relevant for the conservation of biological diversity and to promote their wider application with the approval of knowledge holders and to encourage equitable sharing of benefits arising out of the use of biological diversity.

The establishment of the CBD Working Group on Article 8(j) and Related Provisions in 1998 resulted from intense and effective lobbying efforts of Indigenous Peoples. The Working Group provides a forum for Indigenous Peoples, local communities, and other nonstate actors to participate in similar ways as states, albeit without the right to vote. Even though states must endorse their proposals, the space and instruments created for Indigenous Peoples in the CBD negotiations are “unprecedented” in the environmental arena (Schabus, 2017). Furthermore, considerations relating to the traditional knowledge of Indigenous Peoples have been incorporated into all the programmes of work under the Convention. Under its programme of work to implement the commitments of Article 8(j), the CBD has adopted a number of key voluntary guidelines:

- Akwé: Kon Voluntary Guidelines for the conduct of cultural, environmental and social impact assessments regarding developments proposed to take place on, or which are likely to impact on, sacred sites and on lands and waters traditionally occupied or used by Indigenous and local communities

- Tkarihwaié:ri Code of Ethical Conduct to Ensure Respect for the Cultural and Intellectual Heritage of Indigenous and Local Communities

- Mo’otz Kuxtal Voluntary Guidelines for the development of mechanisms, legislation, or other appropriate initiatives to ensure the “prior and informed consent,” “free, prior and informed consent,” or “approval and involvement,” depending on national circumstances, of Indigenous Peoples and local communities for accessing their knowledge, innovations and practices, for fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the use of their knowledge, innovations, and practices relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity, and for reporting and preventing unlawful appropriation of traditional knowledge

- Rutzolijirisaxik Voluntary Guidelines for the repatriation of traditional knowledge relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity

The adoption of the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-sharing was a milestone in the recognition of the intrinsic link between genetic resources and Indigenous knowledge and associated rights. The Protocol is the first multilateral environmental agreement with substantive provisions on Indigenous rights (Schabus, 2017, p. 271). It states that traditional knowledge and associated genetic resources can only be accessed with the prior informed consent (PIC) of Indigenous Peoples, and if such access is authorized, fair and equitable sharing of benefits must be ensured.

But challenges to integrate Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge and worldviews in the environmental field continue, as illustrated by experiences at the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). IPBES embodies “one of the most ambitious attempts to date to bridge the divide between scientific and indigenous and local knowledge” (Löfmarck & Lidskog, 2017 p. 22). To bridge this divide, IPBES established a task force on Indigenous and local knowledge systems, methodologies and an approach to recognize and work with Indigenous and local knowledge across all its assessments, most recently for those on sustainable use of wild species, values of nature, and invasive alien species. However, IPBES struggles to live up to its ambitions within the confines of the Western scientific system. For instance, it focuses mainly on the inclusion or exclusion of different actors instead of how their visions and values are represented through the selection of authors and evidence for IPBES assessments (Beck & Forsyth, 2020). This matters as power resides with those who frame issues and processes, which for IPBES largely remains with people within the Western scientific worldview.

Adapting to and Mitigating the Climate Crisis

Climate change aggravates the disadvantages already faced by Indigenous Peoples, including human rights violations, poor socio-economic conditions, and discrimination (ILO, 2017). At the same time, measures to address climate change, such as the construction of dams, biofuel plantations, tree farms, and nuclear power plants can also have negative effects on Indigenous communities, including by restricting access to their land and natural resources. Such measures often lead to a rise in land grabs, disruption of traditional practices, and community displacement (Recio & Wallbot, 2017). Indigenous Peoples’ participation in climate politics is key to reducing the risks to their livelihoods.

Indigenous Peoples have criticized the predominant Western understanding of climate change, which they see as a result of the same mindset that promoted the exploitation of people and resources during colonization (Gram-Hanssen, Schafenacker & Bentz, 2021). Their historic experience and holistic perspective of nature-human relationships makes them key agents in developing climate solutions.

However, the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) did not include any reference to Indigenous Peoples and they were not formally recognized as a constituency in the UNFCCC until 2001. In 2008, the International Indigenous Peoples Forum on Climate Change (IIPFCC) was established as the caucus for Indigenous Peoples participating in UNFCCC processes. They have lobbied, unsuccessfully so far, for equivalent participatory rights to states, including through a working group on Indigenous Peoples, similar to that of the CBD Working Group on Art 8(j) (Powless, 2012).

The UNFCCC continues to marginalize Indigenous knowledge in the climate discussions (Comberti et al., 2016), with the 2015 Paris Agreement failing to fully recognize the role of and the need to further integrate Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge and practices in climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts. One case in point is an initiative under the UNFCCC called Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+). REDD+ intends to financially compensate developing countries for keeping their standing forests and has raised huge but short-term expectations for funding. However, much of the standing forests in the developing world are inhabited by Indigenous Peoples (Frechette et al., 2016). Implementation of REDD+ can therefore cause severe constraints to their access to forest resources, affecting traditional livelihoods and aggravating their socio-economic conditions. But Indigenous Peoples were barely considered in the initial proposal.

Only when the last tree has died and the last river has been poisoned and the last fish has been caught will we realize that we can not eat money.

Indigenous Peoples’ efforts played a pivotal role in the adoption by the UNFCCC of the 2010 Cancun Safeguards, which recognize the need to ensure respect for the knowledge and rights of Indigenous Peoples, although avoiding the term “traditional knowledge.” The Safeguards require “the full and effective participation of relevant stakeholders, in particular, Indigenous Peoples and local communities,” instead of acknowledging Indigenous Peoples’ right to the free, prior, and informed consent called for under UNDRIP.

REDD+ was also criticized by Indigenous Peoples as grounded on a materialist and simplistic view of forests. Some communities in the Amazon have put forward an Indigenous version of REDD+, based on a traditional combination of productive use of the forest with simultaneous protection (Alonso, 2016). The proposal in Peru, for example, is principled on the primacy of collective rights of Indigenous Peoples, including to self-determination, consent, and lands. However, as Dupuits and Cronkleton (2020) argue, these initiatives must still overcome fragmented institutional governance of forests and continued challenges related to Indigenous tenure security.

Beyond Inclusion for Improved Outcomes

Indigenous Peoples are critical to sustaining the diversity of life on Earth. Many Indigenous Peoples are at the frontlines of resisting the drivers of the global environmental crisis. During the Glasgow Climate Change Conference in 2021, the Guardian highlighted the leadership of six young Indigenous women, arguing that Indigenous Peoples have done more than any government to solve climate change. Yet, international and national policies and laws do not recognize and support their collective rights (Tauli-Corpus et al., 2020). Respecting their rights and ensuring sufficient legal and financial support for their significant role as guardians of nature, culture, knowledge holders, and agents of change is essential, and a necessary first step.

It is time to get serious about Indigenous Peoples’ leadership and integrating new and traditional knowledge to create solutions—and systems—that work both for people and the planet. If the international community is to succeed with its sustainability agenda, it matters what worldviews underpin its creation and control. If Western cultures continue to subjugate Indigenous knowledge, humanity’s collective future will be compromised. It took many years for Indigenous Peoples to put forward their rich and long-lasting traditional knowledge and worldviews in the international arena. Indigenous Peoples are willing and able to lead and “require only that other... actors... sit down and talk—or simply catch up” (Powless, 2012, p. 421).

If traditional knowledge is integrated with other scientific and technological knowledge, innovative and equitable ways of creating a better future for all can be found. An example is the AI Laboratory, which develops and applies Indigenous protocols to the making of artificial intelligence based on caring for country and kin. The IPBES assessments, the post-2020 global biodiversity framework, and implementation of the Paris Agreement on climate change present significant opportunities for further dialogue, leadership, and convergence in the international arena. A key question is whether the international community will finally have the courage to move away from the status quo and follow the lead of Indigenous Peoples.

Works Consulted

Alonso, J. (2016). Colombia, Ecuador y Perú apuestan por incluir un enfoque indígena en la gestión de los bosques. p.dw.com/p/1IsR5

Beck, S., & Forsyth, T. (2020). Who gets to imagine transformative change? Participation and representation in biodiversity assessments. Environmental Conservation, 1-4. doi.org/10.1017/S0376892920000272

Comberti, C., Thornton, T., & Korodimou, M. (2016). Addressing Indigenous Peoples’ marginalisation at international climate negotiations: Adaptation and resilience at the margins. Social Science Research Network. doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2870412

Crossen, J. (2017). Another Wave of Anti-Colonialism: The Origins of Indigenous Internationalism. Canadian Journal of History 52(3), 533-559. doi.org/10.3138/cjh.ach.52.3.06

Daes, E-I. (2000). Indigenous Peoples and their relationship to land. E/CN.4/Sub.2/2001/21. digitallibrary.un.org/record/419881?ln=en

Daes, E-I. (2009). The contribution of the Working Group on Indigenous Populations to the genesis and evolution of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. In C. Charters & R. Stavenhagen (Eds.), Making the declaration work (pp. 48-77) IWGIA.

Dahl, J. (2012). The Indigenous space and marginalized peoples in the United Nations. Palgrave Macmillan.

Dupuits, E., & Conkleton, P. (2020). Indigenous tenure security and local participation in climate mitigation programs: Exploring the institutional gaps of REDD+ implementation in the Peruvian Amazon. Environmental Policy and Governance 30(4), 209-220. doi.org/10.1002/eet.1888

Frechette A., Reytar, K., Saini, S., & Walker, W. (2016) Toward a global baseline of carbon storage in collective lands. Rights and Resources Initiative. rightsandresources.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Toward-a-Global-Baseline-of-Carbon-Storage-in-Collective-Lands-November-2016-RRIWHRC-WRI-report.pdf

Gram-Hanssen, I., Schafenacker, N., & Bentz, J. (2021). Decolonizing transformations through ‘right relations.’ Sustainability Science. doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-00960-9

Löfmarck, E., & Lidskog, R. (2017). Bumping against the boundary: IPBES and the knowledge divide. Environmental Science & Policy, 69, 22–28. doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.12.008

Powless, B. (2012). An Indigenous movement to confront climate change. Globalizations 9(3), 411–424. doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2012.680736

Schabus, N. (2017). Traditional knowledge. In E. Morgera & J. Razzaque (Eds.), Biodiversity and nature protection law (pp. 264-279). Elgar.

Tauli-Corpuz, V. (1999). Thirty years of lobbying and advocacy by Indigenous Peoples in the international arena. Indigenous Affairs 1, 4–11.

Tauli-Corpuz, V., Alcorn, J., Molnar, A., Healy, C., & Barrow, E. (2020). Cornered by PAs: Adopting rights-based approaches to enable cost-effective conservation and climate action. World Development 130, 104923. doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.104923

Wallbott, L., & Recio, E. (2018). Practicing human rights across scale: Indigenous peoples’ affectedness and recognition in REDD+ governance. Third World Thematics 3(5–6), 785–806. doi.org/10.1080/23802014.2018.1599691

Additional downloads

You might also be interested in

From Land Degradation to Land Restoration

Combating desertification, land degradation, and droughts can win socio-economic benefits for people in drylands and reduce climate change impacts.

The Rising Pressures on Ocean Governance

The ocean is under serious threat. Stressors include overfishing, marine pollution, habitat destruction, and acidification.

National State of the Environment Report: Uzbekistan

The National State of the Environment Report (NSoER) is a comprehensive document that provides a snapshot of current environmental trends in Uzbekistan's socio-economic development for citizens, experts, and policy-makers in the country of Uzbekistan.

On Behalf of My Delegation (Second Edition)

This backpacker’s guide to the world of climate change negotiations sums up key challenges faced by negotiators and ways to overcome these problems.